In Year 2002 i attempted to build what i thought was a better steam engine. The idea was to heat water in a chamber, expand a water piston (there goes the efficiency, as hot steam condensates with cold water piston) and do some turbine work with the cold water from the piston. The twist, i thought, would be to cool the hot water chamber after all the water has been emptied in the previous way, and create a vacuum to suck cold water back, thereby doing the reverse of the above and generating ‘extra’ surplus energy conversion. Later i realized what i was attempting was an engine design popular before James Watt, called the Newcomen Atmospheric Engine invented by one Thomas Newcomen. But it suffered hugely from all thermal inefficiencies. Luckily my hodge-podge contraption didn’t work and my parents were relieved that i could now focus on the 12th Standard board exams and hoped that by some of their many gods’ grace, i would pass it.

In 1st year BSc, i made a model boat with hollow hulls such that they would trap air and reduce surface drag. Unfortunately i don’t have any photos of it.

As my final year project for Bachelor of Science, i and my friend Mukesh Bachhav hacked my father’s old Bajaj Priya scooter to learn about the engine by fooling with it as well as modifying the 2-stroke engine into a 4 stroke one. It didnt work at the time because it was badly engineered (we never trained as engineers), but it helped me many years later land up a PhD opportunity!

In 2007 I began working for an NGO called ARTI, on some way to convert the waste heat of a newly designed efficient firewood cookstove into electricity and then eventually into powering LED lights. This need arose because traditional 3 stone cookstoves emitted a lot of light as well as heat. By insulating the heat, the optimized ARTI design lost out on the benefit of free light. Hence this project. The plan was to acheive the goals through Stirling Engines. We built many prototypes. Mostly they didnt work, but eventually some did. However, they never had serious power to achieve our goals.

The ARTI experience kind of hooked me onto the world of Stirling Engines. I built many over the years, but almost all were toys. Here are some.

I wanted to start my prototyping journey in 2010. It was called ‘Jugaad Works’ because i was a person who did a lot of jugaad and didn’t understand or appreciate proper engineering. I built the above Stirling engine as a toy which i could make and sell. It didn’t workout because the design was very finicky and lacked any thought on how to mass produce while keeping the quality as workable. This lasted about 6 months. Then i became bankrupt.

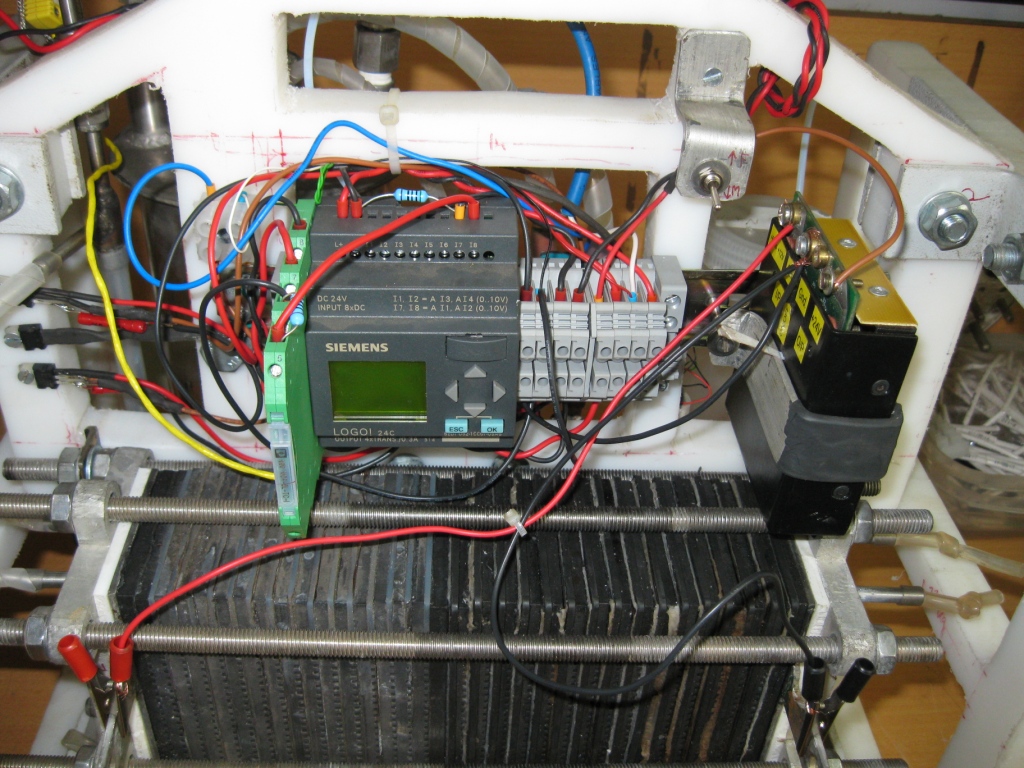

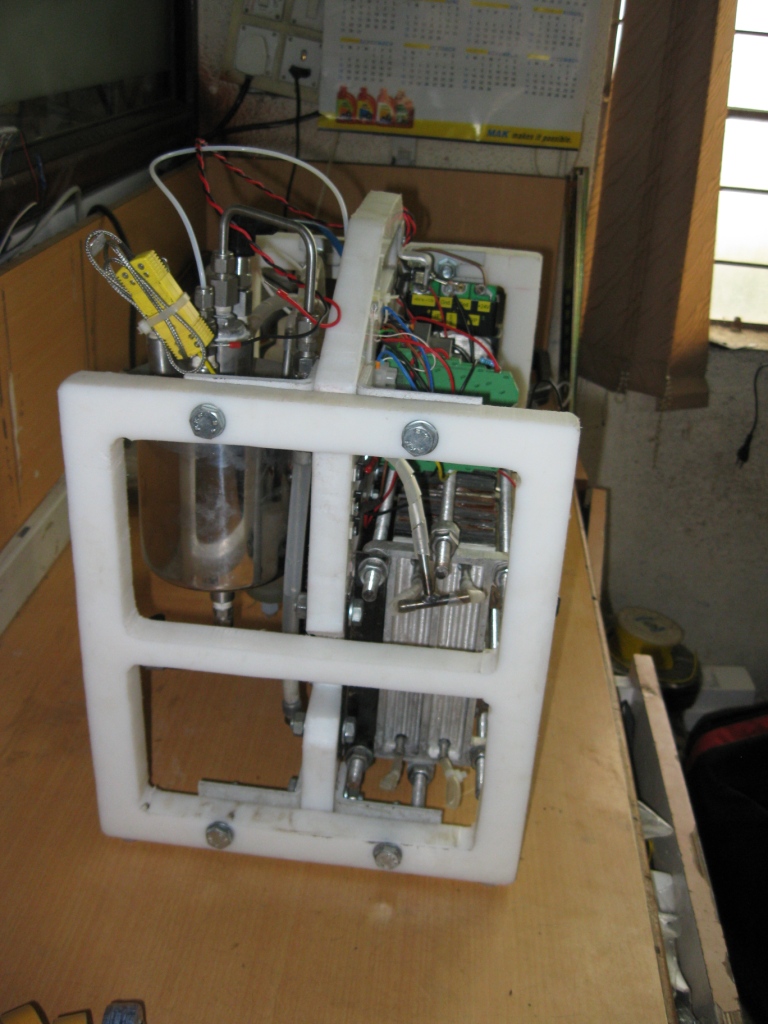

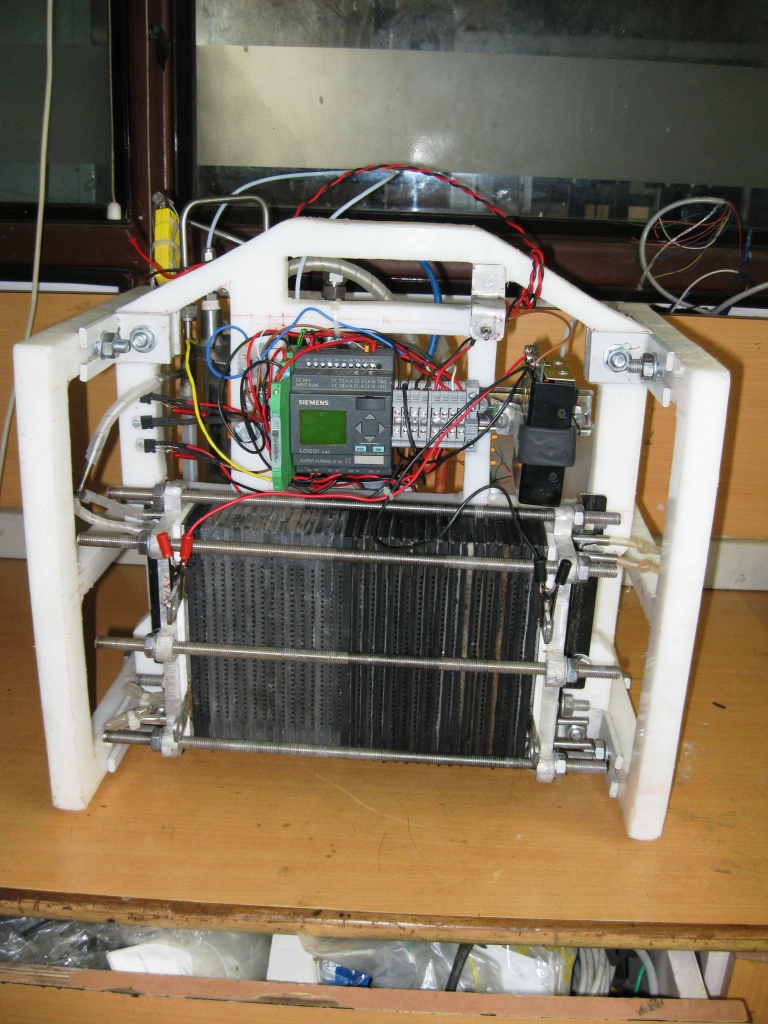

Next, i chose to work for a company for a year. I made a Fuel Cell backpack system for Texol Engineering, Pune. It was the first serious engineering project i did and am very thankful to the company and my mentor-boss Vijaykumar for recruiting someone with no engineering training to actually handle such a complicated task.

The Stirling engines and the experience with fuelcell systems told me that i loved engineering and i should learn it a bit. I tried to search for PhD opportunities in the field of Stirling engines but there weren’t any i could find. Finally i expanded my google search terms and luckily got into a PhD program at Université catholique de Louvain from 2012-2015. My job was to study and test a fantastic idea my supervisors Hervé Jeanmart and Francesco Contino had come up with. The central problem was that in the field electricity generation from of biomass gasification. In a conventional plant of this kind, petrol engines are used to burn the syngas generated from biomass gasification, and since that syngas has a lot of sticky gooey stuff called tars, they used to clog up! This is considered one of the major roadblocks to such technology. Millions are spent on developing gasifiers which will have minimal tar content in their syngas. My supervisors thought in the opposite direction. Tars have an interesting property, they condense into gooey sticky bad stuff at low temperatures, say below 200 C. But above that they are a fantastic fuel! So my supervisors asked – why not use the recently invented HCCI engine to burn syngas, always keeping the temperatures above 200C so that tars wont be a problem? To prove/disprove it was my job. With a great in-house team of technicians, great supervisors, a generous funding by the Belgian Government and a rich learning environment of the university, this is what we made (sorry, video is low quality thanks to my outdated cell phone):

But i also did other crazy stuff while at the PhD scene (my supervisors allowed it for some unknown reason). Here’s something i made for the first European Maker Faire held in Rome in 2013. As my testing guinea pigs would say – it was not so user-friendly.

I also dabbled in vintage photography by buying lots of old cameras, and making cyanotypes! https://flic.kr/s/aHskyVFEC8

Back in India after the PhD, in 2015, i joined the NGO Vigyan Ashram as a coordinator for the newly formed Design Innovation Center. My job was to train young graduate engineers on how to make solutions for rural problems, document them, and so on. Some of the projects i supervised/contributed to:

My design.

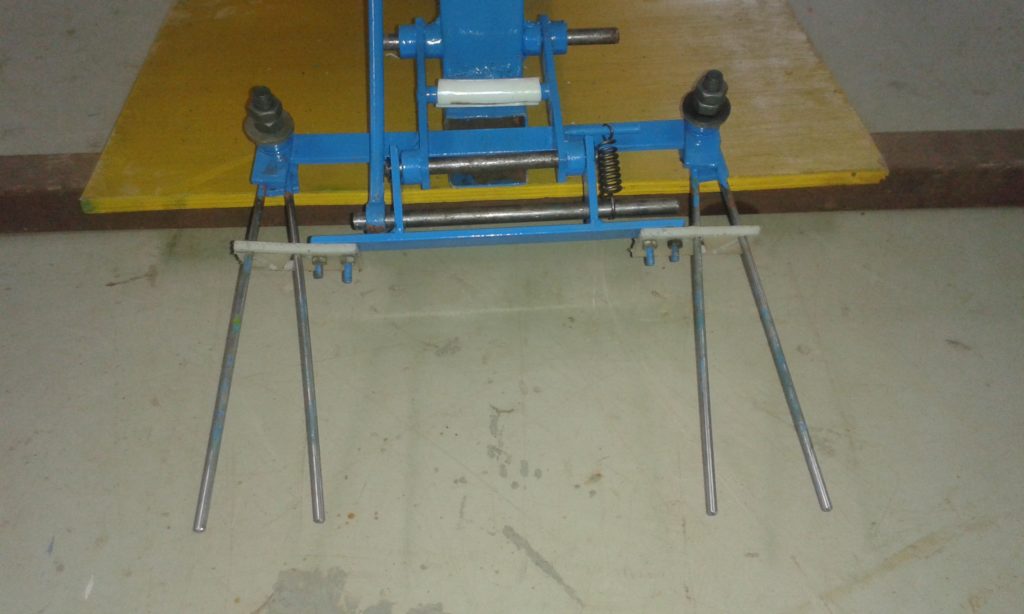

The innovative pincer mechanicsm.

The innovative pincer mechanism

A comparison between Chinese design and ours

Swami Karekar’s first prototype.

While at Vigyan Ashram, i built for the our Fablab team’s FabConference visit something which captured the Indian needs but made with ultra modern FabLab machines – a laser cut Charkha for spinning cotton balls into thread.

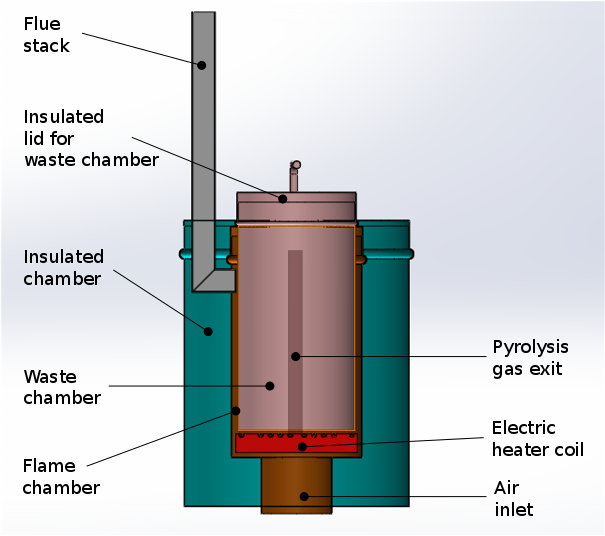

Finally i quit Vigyan Ashram to begin my own protoyping setup in Pune, in 2017. That is the SmallDesign this website is about. One of the first projects was to design an efficient sanitary napkin incinerator. This is where my PhD training as a thermal engineer paid off very well. I could identify the issues with conventional electric heater based designs and improve upon them. Here are some details and an image for reference.

A client wanted a smart looking lemon juicer prototype targeted for a corporate office setting. Here’s what i made:

Abhijeet, my friend and i began making a series of prototypes of a solar spices roaster for CTARA, IIT Powai.

At the behest of Vishal Sardeshpande, the IIT prof who gave us the solar spices roaster project, i launched into making a series of dataloggers and controllers for his upcoming jaggery production plants, solar steam cooking plants, thermal dryer units, etc.

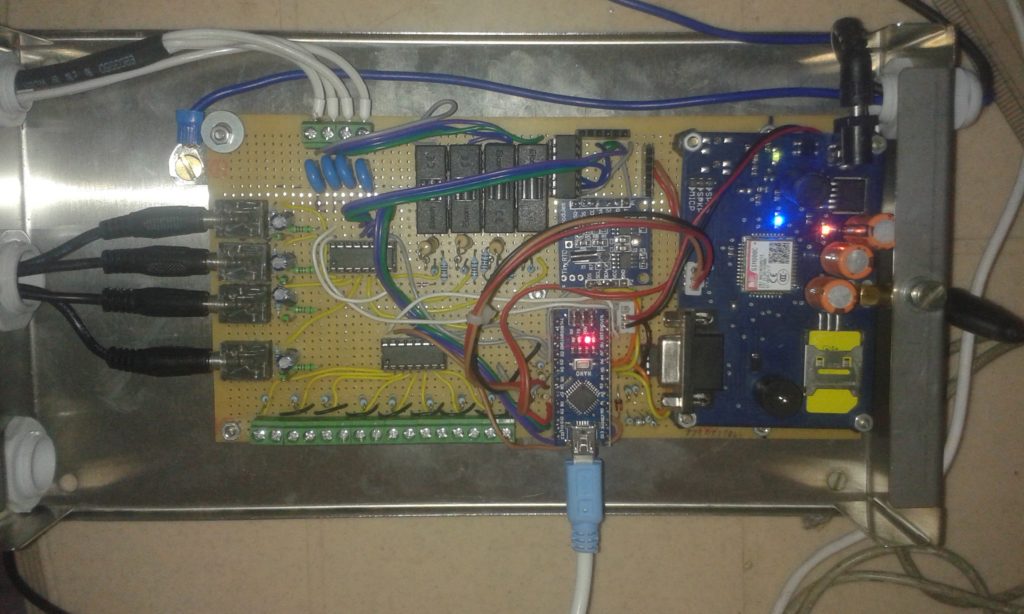

In the first one named SmallDAC 1, it measured many temperatures and power consumption of an electric-solar steam cooking system installed in NCL kitchen. And sent the data to the scientist ever couple of hours over GPRS. This was the first time into serious electronics.

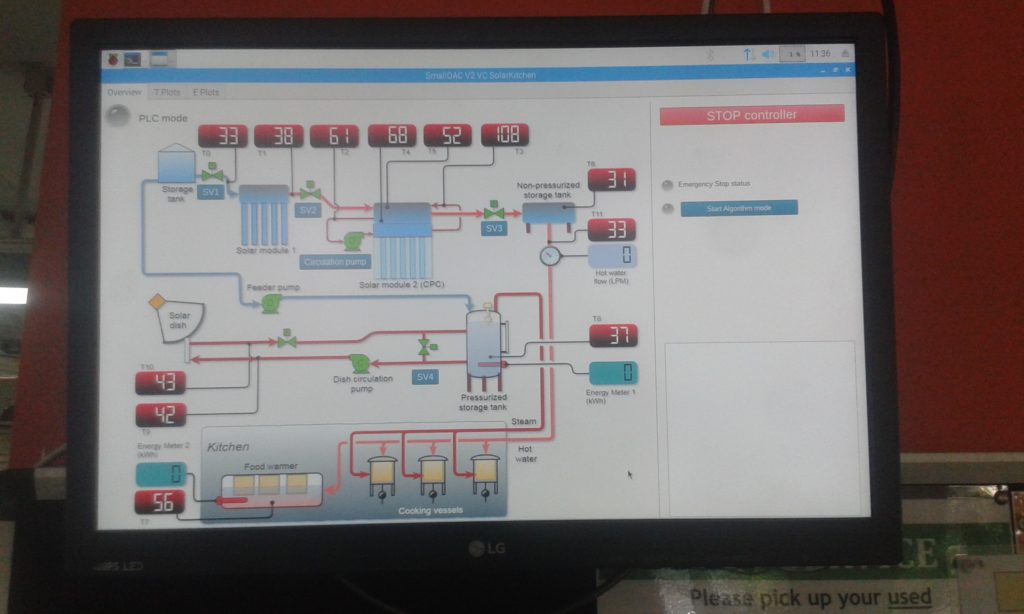

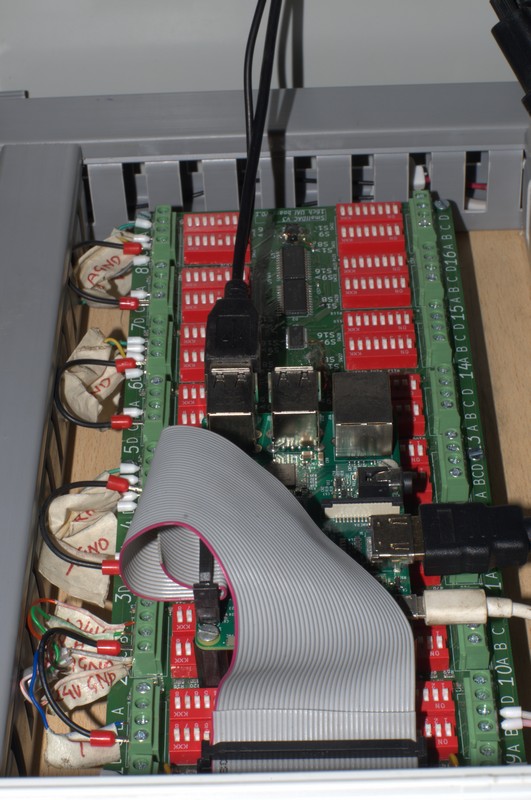

The i made a new system – the SmallDAC V2. It had multiple analog input cards to read temperatures (PT100 and thermocouples), logging, digital inputs and outputs and so on. This modular system was based around a Raspberry Pi. The GUI was based on pyQT5 and the backend was all python. I had to learn all this in a short time of 4-5 months, although i knew a bit of python data processing from my PhD days.

While i had the role of an electronics controller developer, i also assisted where ever my skills in physics or mechanics were needed. Like in the designs of dryers for different clients.

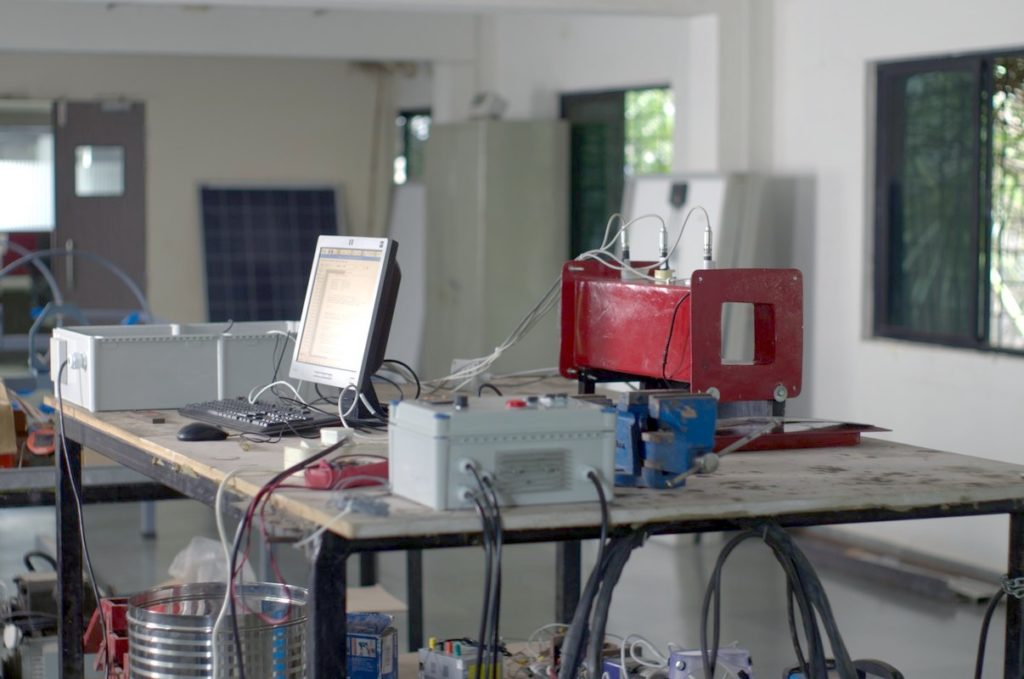

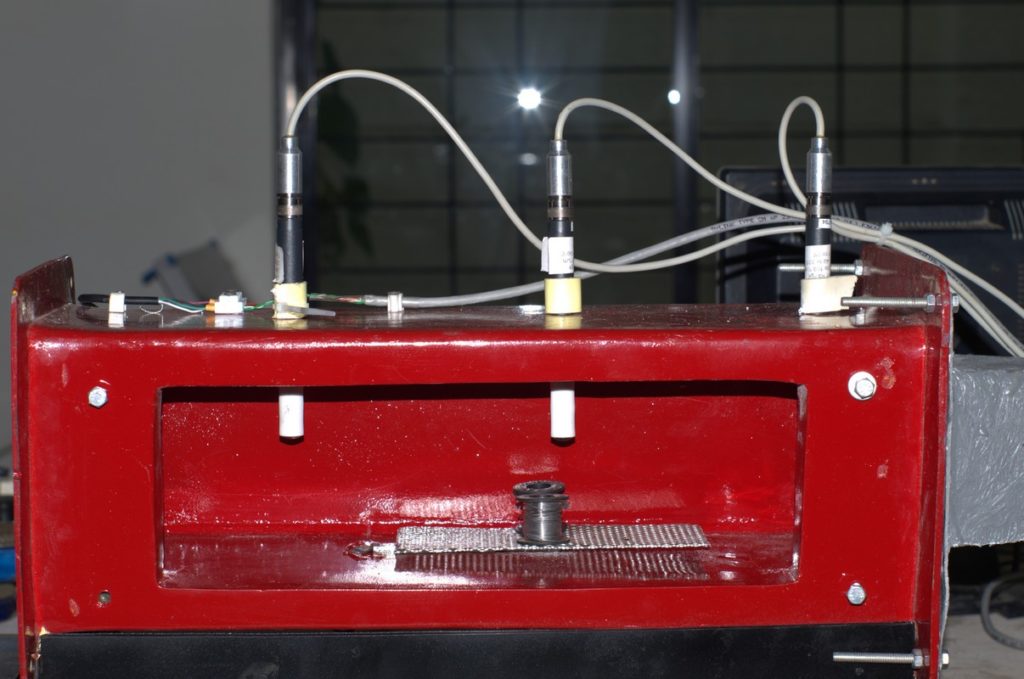

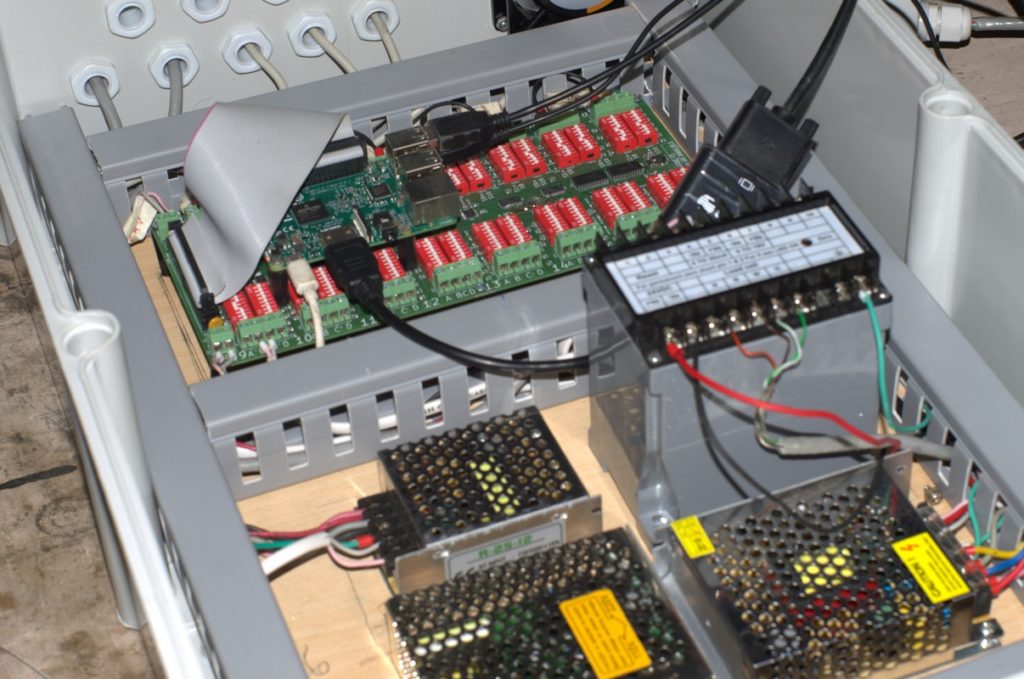

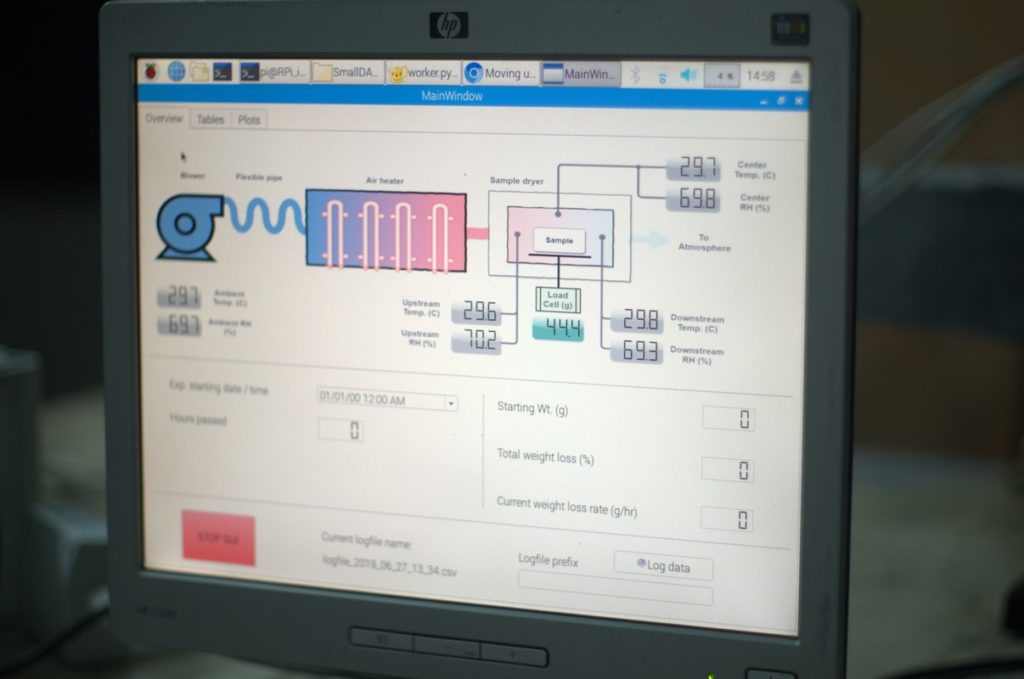

Based on the performance of SmallDAC V2 and its limitations i designed the SmallDAC V3. The first implementation of this controller was for a vegetable drying characterization setup designed by my friend Ameya Kulkarni as part of his PhD studies at ICT/BARC.

Initial test bench.

A weighing scale measures change in mass of sample while T and RH at entry, mid and exit are monitored.

SmallDAC V3

SmallDAC V3 in a control box.

GUI for SmallDAC V3.

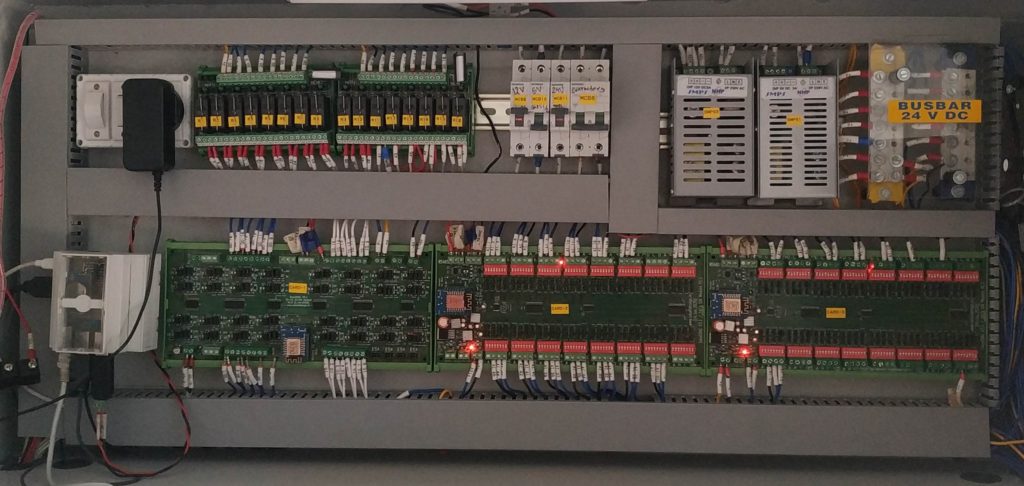

Soon i made SmallDAC V3 with much better characteristics. It was implemented at the 2nd Jaggery Plant of Vishal Sardeshpande’s Sarvaay LLP Ltd. in Wagholi. Pune.

A screenshot of the GUI. Note the instructions in the Devnagri script (bottom right) for the workers working at the plant.

I also am trying to develop a conversion system that could transform the foot pedal based clutch system of a car to something driven by a thumb switch on a gear stick. This is for a client Mr. Shashank Pandhare of Provenant Systems, Pune.

Citizen Science!

Abhijeet and i decided to get into data processing and environmental instrumentation for reasons unknown. We got excited by the work done by IndiaSpend.org which installed low cost air pollution monitoring in New Delhi in 2015. We contacted them, got some info and funds and made our very own Breathe2 sensors. Here’s our first prototype.

Then we realized some of its flaws. And made Breathe2.1. Its details could be found here.

Sumithra Surendralal, my friend and collaborator on this project and i developed the analysis process of the data generated by Breathe2 devices. Here’s our little discovery as to how Pune breathes and when is the good time to take an exercise walk/run?

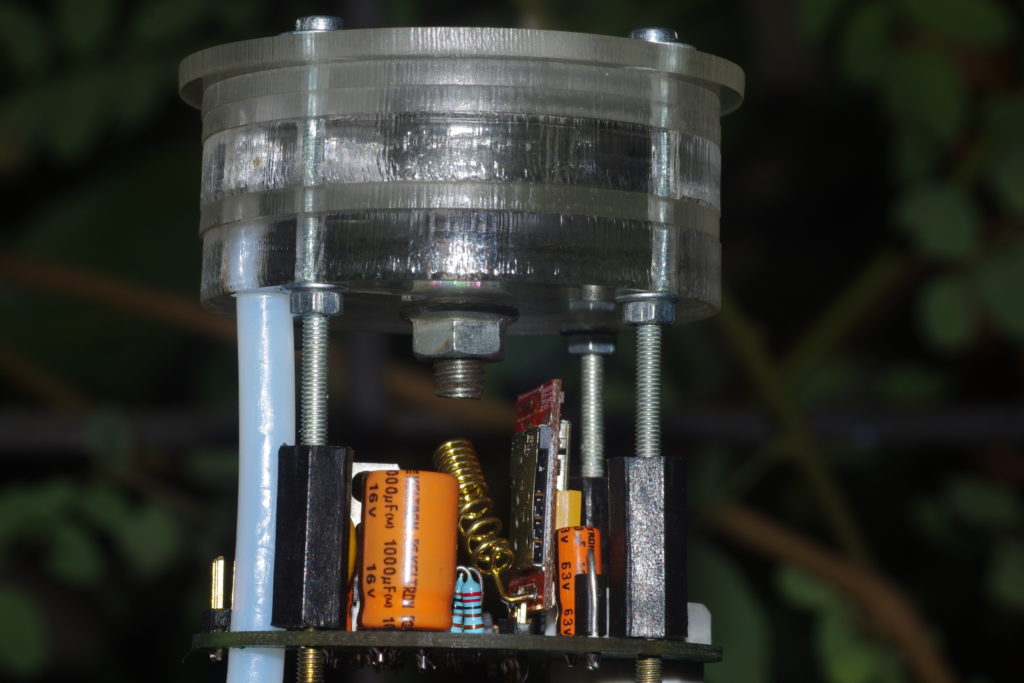

I also wanted to map live rainfall based on the success in implementing online data recording of the Breathe2 above. However i could not complete the RainCloud project due to lack of time and funds. The idea was a device, like below, would auto-empty when filled to a measured volume with rain water. And everytime it empties, a sensor detects this and records the number of times in an hour such events have occured. This data could be sent to a cloud (not the real one, the one in modern human minds) for further processing of live rain in a geographic location.

Electronics and rain measurement unit together.

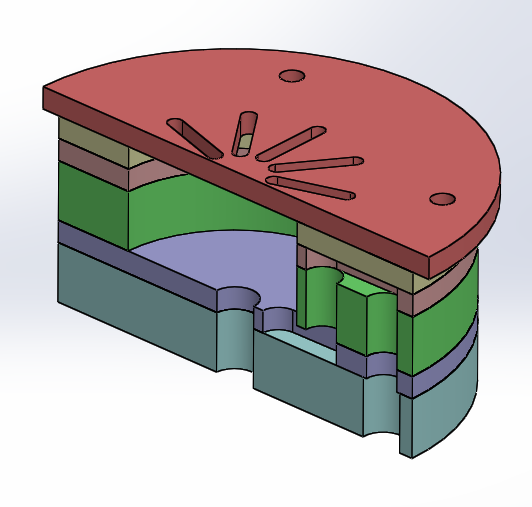

Crossection of the disc type rain measurement device.

Top view of the rain gauge.

Covid 19

After the lockdowns were implemented, i volunteerd with College of Engineering, Pune to develop low cost ventilators. Details here. Eventually my role was relegated to making the controllers for CoEP’s prototypes as there were not many on the team who could do this. So i had soldered them and made some hacks when essential electronics were not available in the market during the lockdowns.

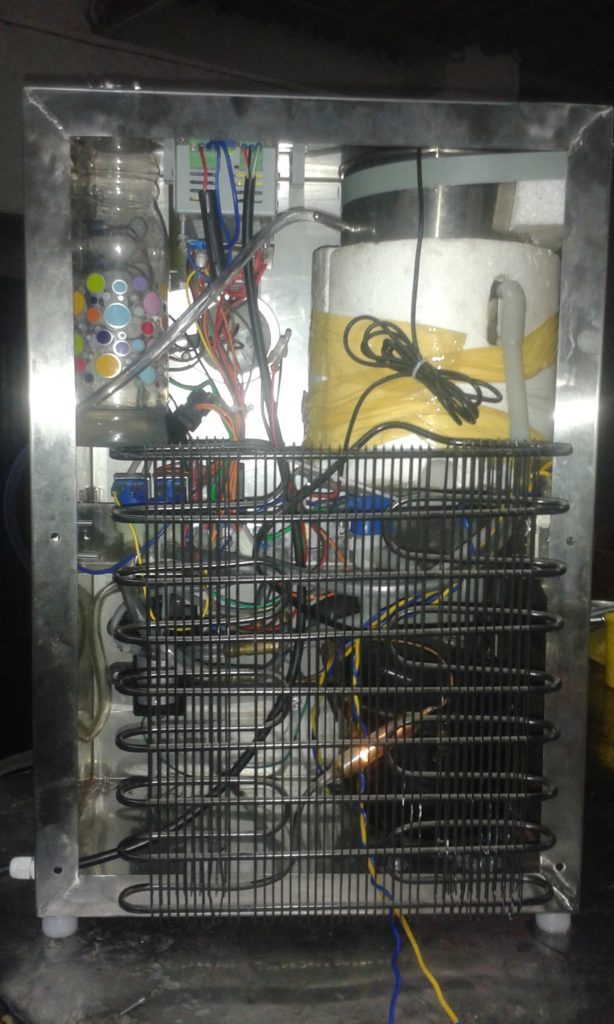

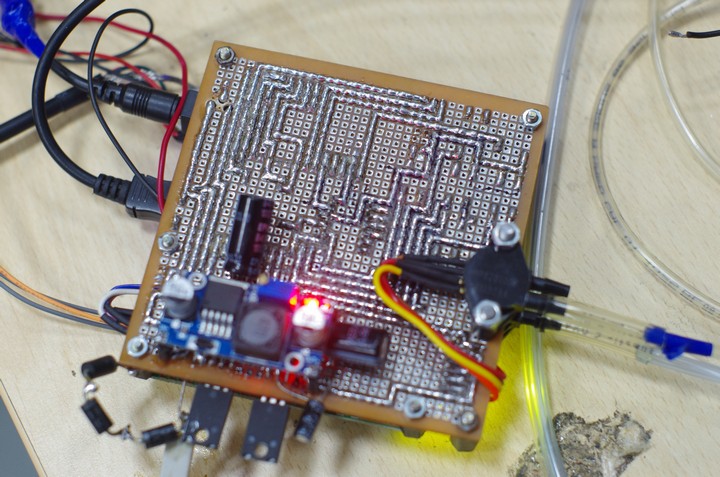

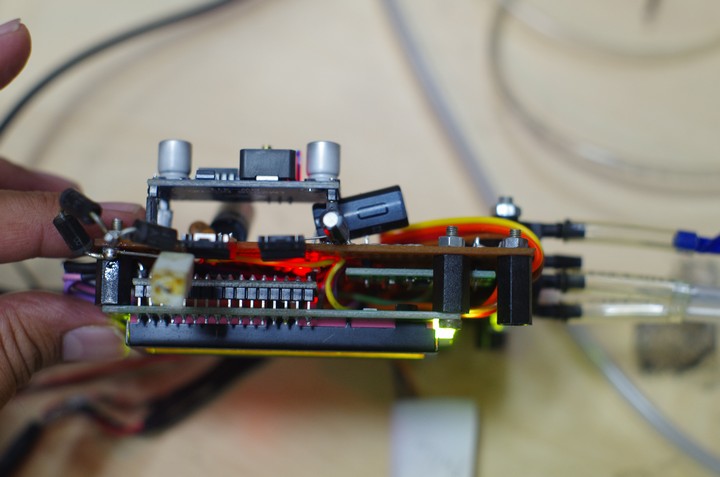

Back side. hand soldered with no schematic plans – just organic mindwork.

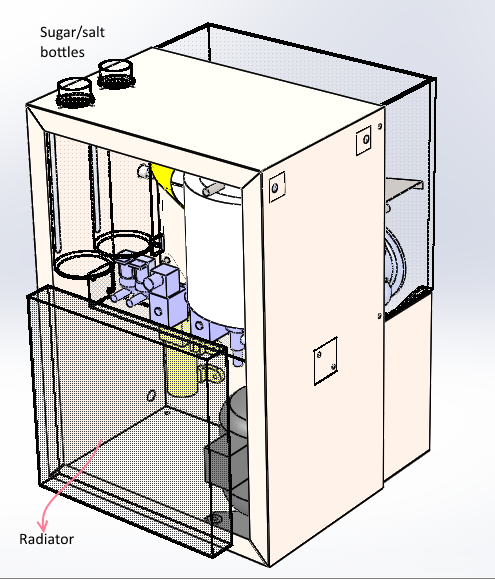

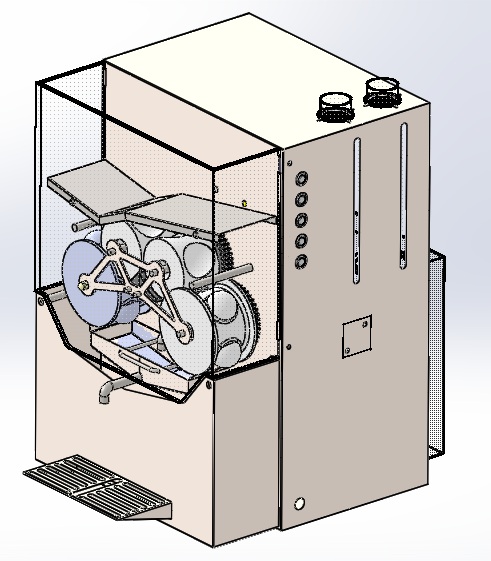

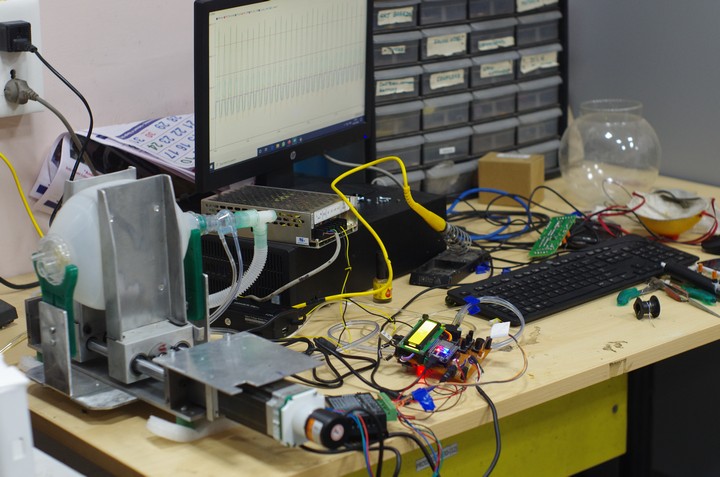

An overview of the ventilator – the 2 ‘crushing’ arms, the AMBU bag, the flow sensor and the controller board.

A side view.

After the success of the above (as much as i could manage given my lack of experience, short project duration, etc), we made a professional PCB with additional features. We are still to test it.

Frugal Science Course (Sep.-Nov.2020)

Thanks to the link shared by my friend Sumithra, i joined Manu Prakash’s exciting Frugal Science course held online every Tuesdays and Thursdays. We learnt about other citizen science projects, scientists working on mind boggling global problems and met a great many like minded people all across the globe. It feels nice to be part of a community. Initially we were asked to list and study and discuss problems all around us which we thought were important and needed frugal solutions. I chose to be a part of 2 groups.

One problem was how to detect elephants who wish to raid farmer’s ripe crops in southern India. Here’s the project page and team video and solutions made by our team.

Another problem i joined in was the immense need of frugal tools for teaching and learning science for those students with Visual Impairments or Blindness. Here’s our team page.